This article is part of a series on today’s philosophies regarding weight change and how digital interventions can help. In this article, we’ll look at the contribution of tracking. The article looks at standards, making sure data meets a useful need, and some particular applications of tracking to metabolic control and diet.

Finding Meaning in Data

Device manufacturers are finding more and more things to track. While some people love measurements such as steps taken through the day, and there’s even a site called Quantified Self exploiting this fad, most people don’t care about data unless they see a direct tie to improvements in their lifestyle. Furthermore, the measurements from devices are not always trustworthy.

How many measurements reported by devices really have medical value? I heard this question from Candice Taguibao, program lead at the nonprofit Digital Medicine Society (DiMe). She works with their Digital Health Measurement Collaborative Community (DATAcc) to find a “core set of measures” that are meaningful, and to standardize how they’re reported.

Taguibao points out that behavioral treatments have traditionally been hampered because the clinician has had to depend on patients’ own reports, which are usually both vague and inaccurate. But as more and more tracking gets built into general-purpose devices such as phones and watches, enormous amounts of data are becoming available. The importance of improving physical activity is underscored by statistics she cites: 81% of adolescents and 25% of adults aren’t meeting WHO guidelines for physical activity.

DATAcc’s goal is to “break down silos in industry around how physical activity is measured using sensor-based digital health technologies,” for easy consumption by EHRs and digital apps. The consortium includes digital tech developers, patient advocates, pharma representatives, academic researchers, and other stakeholders. They produce educational materials to help each group use a standardized, core set of digital measures of physical activity.

DATAcc also collaborates with the Physical Activity Alliance, which created a FHIR standard for the clinical reporting of physical activity. DATAcc aims its core set of digital measures of physical activity at digital health technology developers, care providers, and clinical researchers, while FHIR is aimed at EHRs and other clinical uses. But the two standards aim to be compatible.

A Focus on Metabolism

Lumen is one of the more innovative devices available to consumers. Breathe into it, and by measuring the ratio of carbon dioxide to oxygen in your breath, it can show you how your body is metabolizing its energy. A study has shown the device’s accuracy, matching that of standard measurements for respiratory exchange ratio (RER).

The Lumen device can be part of any program dealing with metabolic conditions such as obesity and diabetes. According to Ulrike Kuhl, a dietician registered by the German Nutrition Association and Head of Nutrition at Lumen, the measurement is used as input into daily nutrition recommendations. The device can also show one’s “metabolic flexibility” over time.

Kuhl explains the concept of metabolic flexibility as follows. “A high-carb diet stimulates the body to release more insulin, which activates the enzymes involved in carbohydrate utilization while simultaneously inhibiting fat utilization. Over time, a high-carb diet will ‘teach’ the body to use mainly carbs for fuel, causing the metabolism to be ‘inflexible.’ When eating a low-carb diet, the body tends to deplete its glycogen stores, and insulin levels tend to decrease. The combination of these two factors stimulates the body to rely more on fat utilization to produce energy. Therefore, Lumen will recommend a lower carbohydrate diet when the body is in high levels of carbohydrate burn and higher volume of carbohydrates when the body is consistently in lower carb burn.”

She says, “To start, Lumen calculates the daily plan by taking into account factors such as age, height, weight, sex, and activity level, as well as the individual health goals of a user. Each morning, a more specific plan is built based on the user’s morning breath measurement. On days when one wakes up in fat burn, Lumen will recommend higher amounts of carbs to help improve carb flexibility. On days when one wakes up in carb burn, the plan will recommend lower amounts of carbs.”

Lumen also collects lifestyle information, such as steps, exercise routines, and heart rates. These enhance the metabolic measurements to refine recommendations for nutrition and lifestyle.

A study that Lumen conducted on its prediabetes program found that over 12 weeks, patients lost an average of nearly 6 kilograms in weight, and decreased their A1C levels by 0.27%.

Digital Support for Food Assistance

I’ll end this article with two companies that help people eat more healthily: the food provider Foodsmart and the medical nutrition therapy and behavior change company Nourish.

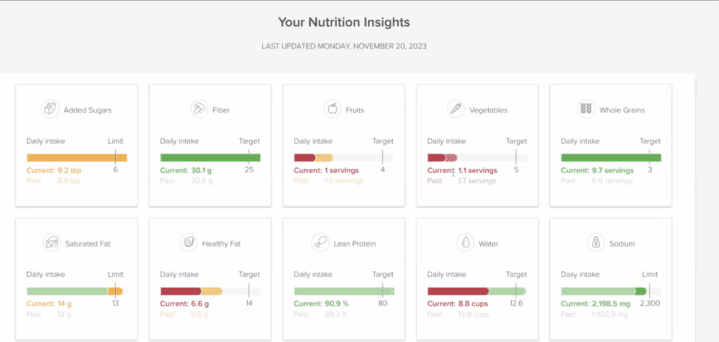

Foodsmart is an end-to-end food-as-medicine and telenutrition provider that helps get food to people who live in food deserts and others who have trouble obtaining healthy foods. Figure 1 shows a screen reflecting a person’s progress toward targets for various foods.

Foodsmart works through healthcare plans, where it is integrated into several large ones. Among their achievements, 39% of enrolled members bring their HbA1c under control after two years, and 33% with hypertension bring their blood pressure under control over an average of nine months. Most of their patients who lose weight have managed to continue doing so after three years.

Foodsmart is not a digital company, but apps and EHR integration enable its effects. They perform telehealth with dietitians and facilitate medical coding. EHRs that work with Foodsmart can preserve their dietary recommendations (foodscripts) as easily as a prescription.

They also identify patients likely to need food assistance by querying the EHR for medical information, including codes related to social determinants of health, traditional diagnosis codes, and prescriptions. They also take in patient-reported information, claims information, and data from other external sources. According to chief executive officer Dr. Jason Langheier, “Some information, like information on diagnosed chronic conditions such as diabetes, is straightforward to link to clinical programs, whereas other types of data require analytics on multiple data points to identify patients where food support is needed.”

Foodsmart also returns dieticians’ visit notes, weight and other biometrics, and other data to the referring physician and to other connected healthcare facilities, so that every healthcare provider can take food-related issues into account. Data that Foodsmart stores into the EHR includes standard biometrics such as weight and blood pressure, indicators on social determinants of health, dietary habitats, allergies, and cultural preferences.

Nourish employs 600 registered dieticians to offer hour-long, one-to-one telehealth visits that are covered by insurance. Its digital support includes monitoring, meal logging, meal planning, nudges, chats with dieticians, and a full library of resources that can be individually deployed based on what the patient’s are working on with their dietician (Figure 2). They measure outcomes both to evaluate the efficacy of individual dieticians and to monitor whole populations of patients to see whether protocols or clinical treatment pathways need to be modified to produce more optimal outcomes.

Dominique Adair, head of clinical quality, says they collect patient reports, data from EHRs, and clinician notes that they mine for food and activity-related information and behaviors, as well as clinical outcomes such as lipid markers, A1C, and blood pressure. In the future, they might also employ claims data and data from devices to continue building out their human-plus-tech solution to disease management.

As the final article in this series I’ll serve up a kind of dessert. We’ll look at digital tracking’s role in maintaining weight loss, and some issues of trust and privacy.

Add Comment