What Hinders Clinicians From Using Technology for Coordinated Care?

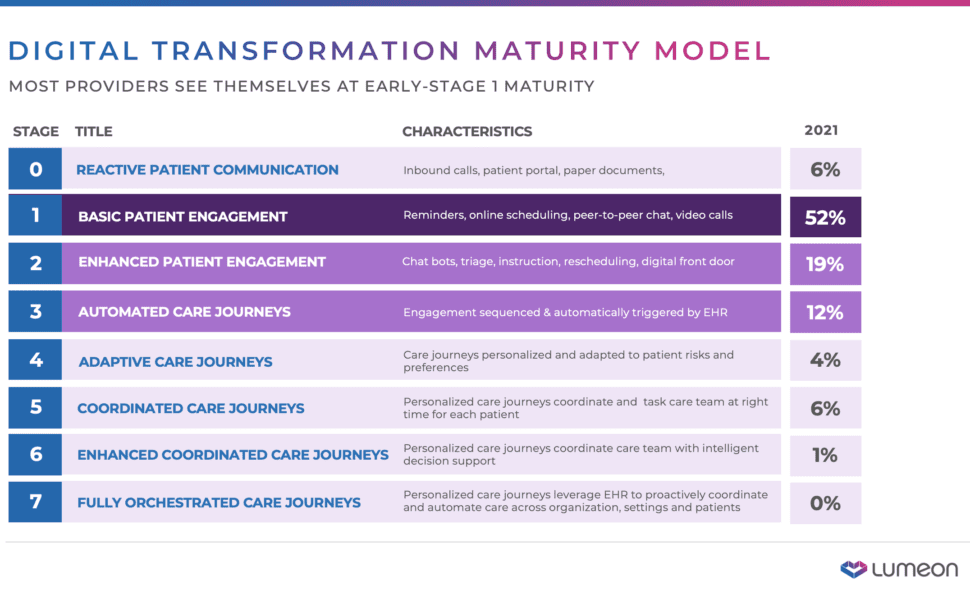

Lumeon, a digital health firm that helps healthcare companies automate their workflows, is circulating a draft of an eight-stage “Digital Transformation Maturity Model” (Figure 1) for discussion. The model traces the use of technology—especially artificial intelligence—to improve patient engagement. In my view, they are going far beyond what most practices consider “engagement,” venturing into remote monitoring, peer support, and self-care. Most clinical practices are very low on the scale, often only in the first step toward active engagement.

I will leave it to the reader to view the Lumeon slides and read about the eight stages there. This article deals with the question I ask in the title—barriers to doing the things recommended in the slides.

Lack of programming and IT staff

You need a carpenter to build a house, and you need computer professionals to implement a digital strategy. Off-the-shelf programs might be available, but you still need to customize a solution and integrate it with all your other IT systems. Lumeon, for instance, offers workflow design support, not just configurable off-the-shelf software.

Good programmers and operators are hard to come by. Most clinical practices are understaffed in the areas of computer training. The market is particularly tight for people who understand sophisticated AI analytics. It’s even more difficult to find experts who are also sensitive to the health care domain and to patients’ oddities, which range from a fear of technology and an annoyance at interruptions to a resistance when given advice.

Payment models divorced from the goals of coordinated care

Most payer systems in the U.S., and even around the world, are still oriented to fee-for-service. If you treat a patient after a fall, you get paid. If you offer guidance to keep them from falling, you don’t.

The U.S. government has been trying for years (at least since the passage of the 2009 HITECH act) to move clinicians to holistic, fee-for-value health care models and coordinated care, such as Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs). Progress has been glacial, and Medicare is constantly searching for other routes to success, tinkering with the ACO program and other initiatives such as requirements for data sharing. Some insurers, meanwhile, have tacked wellness programs onto the old fee-for-service model.

Paying for long-term outcomes is an intrinsically difficult economic puzzle. The closest that the healthcare field has come is to define standards of care and try to help doctors adhere to them. Because many patients have unique and complex combinations of conditions, applying a standard can detract from effective care. So rewarding coordinated care is an unsolved problem.

Lack of time for clinicians and management to give attention to the transition

The lack of attention to coordinated care is a consequence of the payment problems in the previous section. If you could plug remote monitoring, intelligent agents offering customized advice, and other traits of coordinated care into your workflow as add-ons, everybody would probably do it. But the move to coordinated care isn’t like that—it involves a total rethinking of one’s approach to patients, clinicians’ activities, technology, and the business.

I think that many clinicians are tired of the revolving door of high-need patients and would like to move to coordinated care, but it’s not something they can do incrementally, so they just don’t get very far.

Reluctance to do more online engagement because of security concerns

Coordinated care involves new devices collecting a lot of information. Each of those devices must be secured, because many malicious or exploitative organizations would love to get their hands on that data. In fact, many of the manufacturers of the devices are collecting this information and using it in ways of which the patients might not approve.

Furthermore, once collected, this information has to travel over local networks and the Internet to the provider, and sensitive information involving treatment has to flow back. Even if one encrypts the data, even metadata (such as the volume of data flowing) can indicate a problematic health condition and give away information that shouldn’t be known to snoopers.

These problems are reasonably solvable (although digital systems always have a certain level of vulnerability), but doing so requires care and expertise.

Silo’d technology

Coordinated care requires different systems—EHRs, scheduling, data analytics, billing—to work together. It’s hard to integrate the systems into an orchestrated patient experience.

In particular, current EHRs are designed to collect data for billing. Secondarily, they accumulate information that is useful for clinical care, but they aren’t set up to provide the kinds of analytics that are needed for remote care. The EHRS are opaque, so clinicians cannot make substantive changes to meet the new needs of coordinated care. Technological change, just like management change, must be driven by improved payment models.

Lack of experience using AI

Traditional programming is hard enough to get right. But careful testing can determine that the program meets requirements. Artificial intelligence introduces entire new levels—even new dimensions—of ambiguity and chances of error. The danger of bias in AI, for instance, has become a public concern, widely documented.

The fact is that nobody knows exactly what an AI model is doing. The data scientist feeds in thousands of parameters (known as dimensions or features in AI lingo) and out pops a model that applies them appropriately—or so one hopes. AI systems are improving their accountability, also known as explainability. But to call the models correct, all you can really do is compare them to new data. Thus, part of AI development is to run completed against test data. But this practice can simply reinforce old biases, or the inaccuracy of the data that was collected.

Furthermore, conditions are constantly changing. Data collected before the COVID-19 pandemic is probably useless now, for instance. And data collected by one hospital is probably inappropriate for another hospital, because they deal with different populations having different lifestyles. So AI models must be routinely run on new data that is carefully vetted to make sure it reflects the conditions a hospital is dealing with.

Thinking of immediate and short-term tasks

Organizations are automating tasks that are obvious because the staff have been doing them already manually. For instance, reminders can be texted to patients before a visit. But few organizations raise their eyes and take in the whole landscape of tasks. It’s time for end-to-end thinking, starting for instance from a prediabetes testing procedure and then going to a referral, a diabetic prevention program, and ongoing monitoring.

Lack of expertise in designing digital care delivery

Technology, however spiffy it is, must serve the needs of the patients. Although doctors are pretty aware of their patients’ needs in general (better diet, better sleep, etc.), they need to rise to another level of sophistication to fashion these goals into a treatment plan. Then the plan must be delivered in bite-sized, actionable pieces—for instance, “Eat a piece of fruit with breakfast today.”

Coordinated care is a new discipline, still being explored. It’s health care, product design, and technology all woven together.

Lumeon’s stages show that many innovators in health care know where we want to go. The hurdles to progress must be tackled with determination—and with optimism, because a better system is possible.